At the end of April, on Independent Bookstore Day, I had the absolute honor of helping to pull together an event—a teach-in and reading for the Midwest Immigration Bond Fund at Pilsen Community Books here in Chicago.

I’ve been on the board for MIBF for about three years now—it’s a brand new organization, begun in 2020, and dedicated to helping people get bonded out of immigration detention, so they can be with their families and communities while they wait for their cases to proceed through immigration courts. I want to talk a little more about the process of immigration bonds, and how, precisely they work in a bit, but first, more about the event.

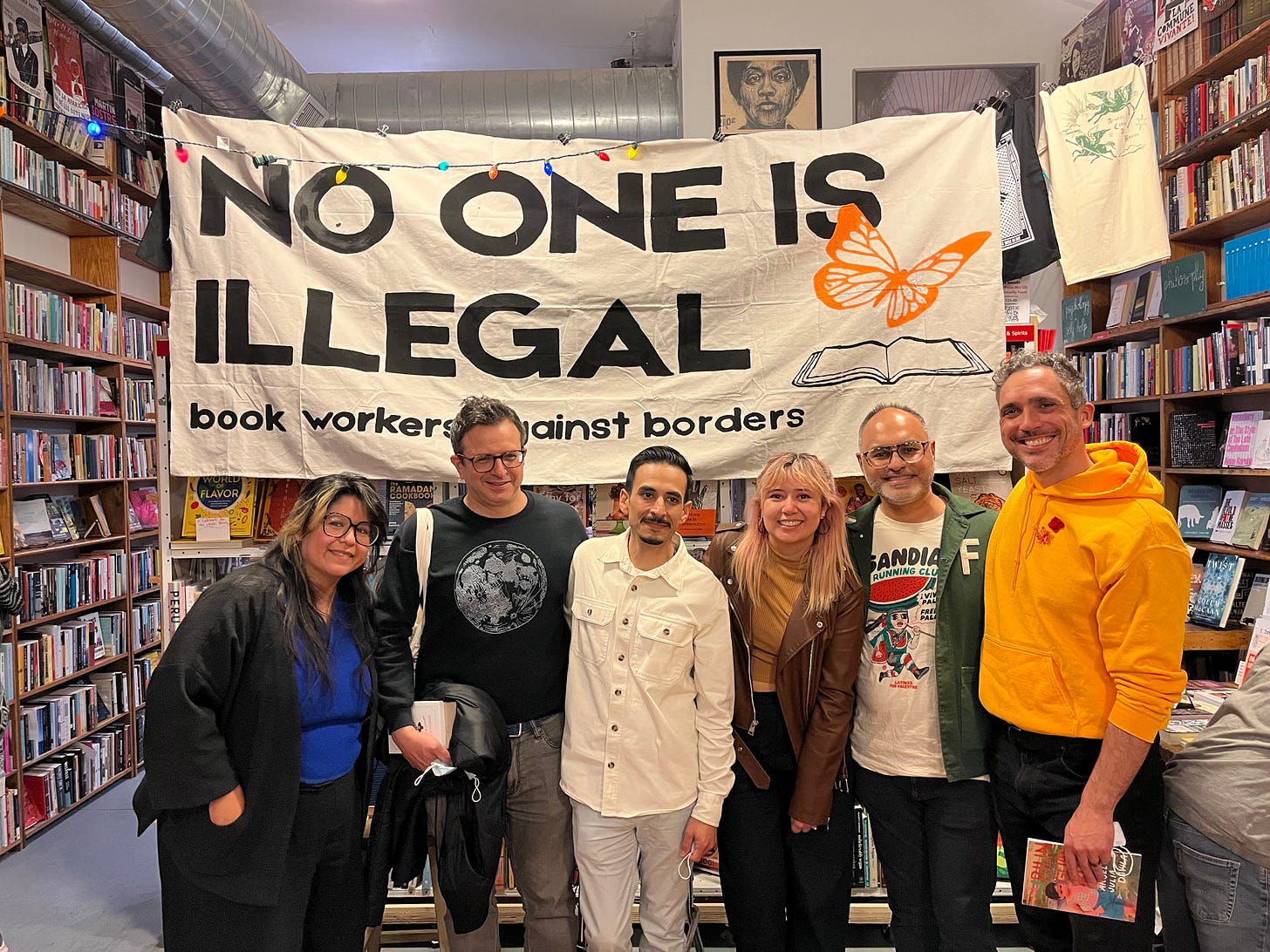

We pulled this together in a matter of about 6 weeks—securing the incredible group of readers pictured above, pulling together a poster for PCB to sell in-store as they do every independent bookstore day, with artist Evangeline Stott. Everyone we asked to participate in this event said yes immediately, and in ways that were overwhelmingly generous and kind—drumming up the event on social media, bringing stickers and zines to give to donors (thank you Angelica!). I showed up early to the event, while PCB was still mid-Independent Bookstore Day madness, and I’ve never seen the store more crowded, a full hurricane of excited chatter and book buying, people perusing the posters and the tote bags, stocking up.

The end of April feels like the first time that spring has really started to happen in Chicago, and so there was some energy of people emerging after long, weird winters, rubbing elbows and ready for togetherness in a way that winter doesn’t usually encourage.

And then, our event started, and it was also packed full, every seat in the house taken, people leaning up against the back wall. Each one of our readers was phenomenal—from Daniel Borzutsky, who read from his book The Murmuring Grief of the Americas, to Diego Baez, who read some poems about Formula 1 and whiteness, Marcelo Hernandez Castillo, straight off another event from Chicago Public Library, read from his book, Cenzontle, Angelica Julia Dàvila read from her new book, Bilingual Bitch, I read from my own book, Rivermouth, Faisal Mohyuddin closed us out with a poem about the way that carcerality has touched on his own family. And somewhere in the middle, two members of MIBF’s board ran a teach in, where they asked each other and the audience why immigration detention is a horrifying institution, how bonding people out works, what, exactly, we do with your money when you donate, how the crowd wants us to show up in the community.

Evangeline Stott’s poster, still available in person at Pilsen Community Books.

It felt like a real conversation, a real community gathered in that space, like all of us, that had spent the winter worrying about this new administration, about the challenges ahead suddenly were able to see each other face-to-face, have our anxieties soothed by the fullness of the room, by the number of people dedicated to these same issues, the number of folks ready to show up on a Saturday night to read and learn and give.

That night, we raised about $3,500—the average bond in the Chicago immigration court is $5,000. Sometimes lower, sometimes higher. A good portion of this was from Pilsen Community Books donating 10% of their sales to us that day—10% of every book and tote and card and sticker, going to help someone get out of immigration detention.

I’ve been to a detention center—I’ve written a little bit about it here, more in my book. They’re prisons, by another name. Big and noisy and overwhelming, and people get lost in them all the time. Nine people have died in immigration detention since Trump took office in January. Countless others will face ongoing medical needs as a result of time spent in immigration detention—diabetes because of poorly regulated food, heart and breathing problems developing into chronic heart failure, mental health crises, blindness due to untreated syphilis, and more. Detention is disabling, and the longer someone spends on the inside, the more likely they are to face these lifelong consequences.

Beyond that—immigration detention separates families, just like deportation does. I’ve helped nervous parents fill out emergency custody forms, detailing who their kids should go to in the event of their own ICE arrests. I’ve talked to parents who have lost custody of their kids because of the destabilizing force of a stint in detention—losing precariously held jobs, housing, and along with them, the right to care for their kids.

People who end up in ICE detention are often there in a few different circumstances. The first is after serving time for a criminal offense—sometimes something as small as shoplifting, drug charges, or a DUI—they essentially are taken back into prison to await their immigration cases, serving double time for the same offense that a citizen would only serve a single term for. They could be people who have never committed a crime and are picked up by ICE at a workplace raid, or driving down the street, or, in the last few weeks, for showing up to court to plead their asylum cases. Only those who do not have criminal offenses are eligible for bond.

The amount of a single bond can be absolutely prohibitive for these families. Something like 60% of Americans don’t have the money to cover a $1,000 emergency right now—much less families that are made up of mixed-status people, some of them forced by immigration status into marginalized, below-minimum wage jobs.

This is where the bond fund, where community comes in. When everyone filling up a bookstore gives $10, $20, $50 dollars, when the bookstore itself slices off a bit of their profits and sends it to us, when artists and people who make beauty decide that part of that beauty is a world with fewer cages and donate their time and money to us—those $5,000 start feeling more achievable.

Getting people out on bond is a thing that you can only do one at a time—you can’t just slide a million dollars across the jailhouse counter and ask them to spring open the doors (or, like, maybe you can but I suspect it wouldn’t end well). It’s slow, painstaking work, and it’s work worth doing because of the way it celebrates the individual person, the right of every single one of us to spend time with loved ones, to be free.

If you’re a fellow midwesterner (here defined by the Chicago immigration court’s service area of Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, and, bizarrely, Kentucky), you can donate to Midwest Immigration Bond Fund here. If you want to help out folks closer to home, check out the National Bail Fund Network.

Alejandra Oliva is an essayist, embroiderer and translator. Her writing has been included in Best American Travel Writing 2020, and was honored with an Aspen Summer Words Emerging Writers Fellowship. Her book, Rivermouth: A Chronicle of Language, Faith and Migration, was published by Astra House, and received a Whiting Nonfiction Grant. She was the Yale Whitney Humanities Center Franke Visiting Fellow in Spring 2022.